Swimming Taupō in February 2024

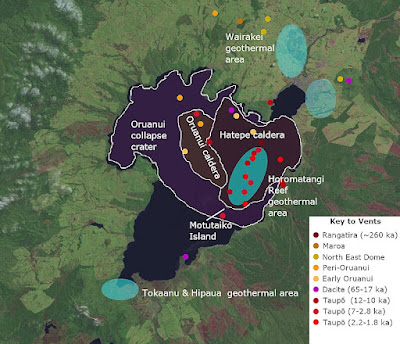

For offshore readers, who may be interested in investigating this swim, Lake Taupō, or Taupō Moana, is the largest lake in the country, located in the central north island, just north the great volcanoes Ruapehu, Tongariro, and Ngāuruhoe of the Tongariro stratovolcanic complex. Lively geothermal activity occurs all around the lake, which is itself a giant caldara. This map shows the location of hot activity, but luckily the water is also very deep in the middle of the lake, so the likelihood of being boiled while swimming is remote. The swim itself is a minimum of 40.2km from Lttle Waihi near Tokaanu to the Taupō Yacht Club at the north end, near the start of Waikato Te Awa (Waikato River). The lake is extremely deep, and the water crystal clear with great visibility. It also tastes nice.

After completing an often-rugged crossing of the Cook Strait at

the end of 2021, and then a very fun crossing of Foveaux in April

2023, Taupō inevitably had to be next, but inexplicably I felt far more

apprehension about this swim than the previous two for various and largely

irrational reasons. I understood that with ocean swims there exist various

factors beyond the control of the swimmer that could bring a swim to an abrupt

or protracted premature end: tides and currents, unpredictable wind, apex

predator activity, and prolonged immersion in cold water are among the most

obvious examples. The warm, safe, and probably serene lake offered none of

these factors (leaving aside the potential for a monumental volcanic eruption) so failure to reach the beach at Taupō Yacht Club could only

be ascribed to some lamentable failure of preparation.

My preparation followed a similar pattern to that of previous

years. In September I made my commitment to the swim with Philip Rush, and

received instructions that despite my enthusiasm for training I should be

reasonable about it, and not go all-out too soon. At that point my weekly

distances were around 24km per week. Some people are interested in

training, and others, quite understandably, are not, so in the interests of

some brevity, I’ve made a separate post about training for this swim.

By the end of January all interested parties said that I appeared

to be physically ready, with the swim date set for around the second weekend of

February. By this stage I felt convinced that I was probably not physically

prepared and resigned myself to some disaster inevitably taking place in the

region of Rangatira Point. Time marched on, and my indomitable support team of

Gráinne and Rebecca (with four Taupo crossings between them, as well as some

solid support experience) exuded enthusiasm and confidence. Finally, we had a swim

date, Monday 12 February, and made arrangements for travelling up to Tūrangi on

11 February. I booked a motel at Tokaanu and made sure my bags were packed.

Come the 10th of February, I went to Pak and Save to purchase the

feed supplies. In the produce area, a problem confronted me: where the kumara

selection is usually arrayed there were ... only potatoes. 'Curious,' I

thought, and went on with my shopping; 'there'll be kumara at Countdown, I go

there next.' I crossed the road to Countdown, and were the kumara usually sits,

I was confronted by a vast display of yams. At this point I started scratching

my head in confusion, and Googled 'kumara shortage'. Sure enough, there

was a national kumara shortage, the result of the cyclones in

early 2023 that wiped out huge amounts of that year's crops and plants. Now,

here was a crisis. Kumara, lightly steamed, formed a critical source of

nutrition for my swims. Rice pudding, and at a pinch, boiled potatoes might be

a substitute, but at such a late stage, I felt certain that the lack of

appropriate root vegetables would spell doom. I alerted the crew, who the next

morning before we departed from Wellington, checked the veggie markets.

Meanwhile, I rang every supermarket in Wellington, and ascertained that

Thorndon New World held a small supply of Red Kumara (Owairaka), which I scooped up.

Travel went smoothly, we checked into the motel, Rebecca and

Gráinne set off to do the car shuttle thing to Taupō and I started preparing my

food and cooking some spuds for dinner. Just before the drivers returned, I

felt I should have a pre-dinner snack; I’d just posted half a sandwich into my

mouth when my phone rang, announcing a problem: Phil had arrived at the

southern end of the lake with the boat and IRB, but the IRB motor had decided

not to start. Consternation! He would have to go back to Taupō to get the motor

checked and fixed, as it was too late to try and do the swim just beside the

big boat. I was happy to swim on Tuesday. Rebecca and Gráinne returned from their car

excursion, generously agreed to the new arrangement and made various adjustments

to their work schedules, while I booked an extra night at the motel.

Come Monday morning we had a leisurely breakfast, went to Little

Waihi for a test swim (I can recommend this, as I learnt in daylight how

slippery the boat ramp was (with the lake’s water levels being very high), as

well as getting to grips with the waterweed forest at the start. We took a

walk, explored all the sights of Tokaanu, and went to Taupō to meet with Phil,

Hana, and Ben for lunch. On the drive, the lake looked friendly and sparkling,

and I didn’t feel at all uncomfortable observing the important landmarks that

I’d swim past the next day. After lunch Gráinne had some very important calls

to make, so Rebecca and I sat at the lakeside for awhile and talked about some

of the great and fast swims that had happened in the past, such as Anna

Marshall’s incredible record, Eliza’s heroic double attempt (during which she

nearly equalled the record on her southbound lap) and other related matters.

At 3:59am on Tuesday 13 February I walked down the slippery boat ramp at Little Waihi, slipped off the side of it with a small scream, and then swam 40.2km to Taupo. As this narrative could become interminable, I’m going to change tack slightly, and consider what went well, what went less well, and how I felt about my modes of execution:

Less than optimal execution

- The Dark: while I had no fear about swimming in the dark (there

was nothing in the water to get me) and have done weekly swims in the dark sea

in Wellington), I found it far more challenging to swim beside the IRB in the

dark than I’d anticipated. I realise that in Wellington harbour, I am used to

the lights and landmarks of Oriental Bay and CentrePort staying still, while I

move past them. Even on very windy mornings with big chop, I can still

orientate myself by these lights – and the red light on the Pt Jerningham

Lighthouse – and swim relatively straight. In the lake, the IRB was lit up like

a Christmas tree, but I was moving and the IRB was moving too, which I found

extremely disorientating. For what seemed like forever, I collided with the

side of the IRB (this can hurt!) and felt as if we were going around in

circles. Try as I might, I couldn’t

straighten myself out. After many collisions, and some instructions (‘we decide

which way you’re going!’) a change of goggles was suggested, so I switched from

the pale blue ones (basically almost clear) to orange goggles. This may have

helped, but I also wonder if the brief pause to change goggles also gave me a

moment to recalibrate in the conditions.

- Referring to ‘the conditions’ brings us to the chop: after about

an hour of swimming, as daybreak approached and brought with it subtle

atmospheric changes, the lake water chopped up. Choppy water is something I’m

familiar with, and some suspect me of deliberately seeking it out. However, the

choppy water in Taupō, while not mountainous, provided different challenges to

the steep, fast northerly ‘ripples’ we get in Wellington harbour and Worser

Bay, or indeed the immensely strong splashy chop I encountered in Cook Strait.

In the sea, there’s usually some direction involved, depending on where the

wind comes from; in the lake the unsettled water had not perceivable direction,

it was just choppy everywhere, with no rhythm. Without the supportive qualities

of salty seawater, it felt as if the water kept trying to bury me. In these

circumstances in the sea I would push my chest downwards, keep my chin down,

and imagine I was swimming down hill, which elevates the feet and legs, but

this didn’t work. Trying to negotiate with this intransigent water quickly lost

its novelty and made it hard to count my strokes.

- My legs: in all

the confusion, my legs started tingling in the weirdest way, feeling

simultaneously heavy and like cotton wool, which I’d never felt before. This

feeling also made it hard to count my strokes and combined with the

disorientation of the darkness and the hectic water, I very quickly became

paranoid that these tinglings certainly indicated a major heart attack or similar

medical catastrophe. The only question was, should I alert the crew to imminent

disaster, or just assume that they’d pull me out? I decided to continue to the

next feed before alerting the crew. When that feed arrived, I made some

enquiries about whether tingling legs were normal, or should I be worried? Phil

said, ‘I’ll check Wikipedia … meanwhile, maybe try using your legs, and they

won’t tingle.’ This bracing advice made me laugh, and we set off again but with

legs that didn’t tingle any more.

- Where's the focus: eventually the chop went away too, but the messy conditions, and a small technical crew hitch that had occurred near the start unsettled me a bit, and I couldn’t get into a good counting situation. In Foveaux, counting my strokes to 200 or 100 was both soothing and motivating, it required concentration and helped me focus on maintaining a good stroke. Evenafter the sun came up and the water calmed, it took time to rediscover this good rhythm. In retrospect, I should have not worried about it for so long. Anyway, once everything was normal again, I announced to the IRB crew, now Ben and Gráinne, that I’d recovered from my crisis, and they kindly said they hadn’t noticed I’d been having one. This point leads me to …

Better execution

- The crisis: not complaining about it while it was happening, and

then re-establishing a nice, happy state.

- The start: I’d felt unsure about how to pace the start of the

swim. I knew from many sources that starting at a conservative pace would be a

recipe for disaster (start slow, get slower; start strong, stay strong). I knew

how to start strongly in the sea, where one also has to get a feel for the sea

state, the strength of the chop, and the wind (this had gone well in Foveaux).

However, I judged the starting pace well, and immediately felt that I had some

strong ‘easy speed’.

- Nutrition: my feed plan remained the same as Foveaux: first feed after an hour, and then every 30 minutes. I would cycle through:

Feed 1: Pouch of mashed banana

with maple syrup and lemon juice.

Feed 2: Two Tasti Snackballs

Feed 3: Some steamed kumara

slices

Feed 4: Two Natural Confectionery

jelly snakes (or dinosaurs?)

A Pure gel every few hours

Drink with each feed: all

warm, a mixture of concentrated Tailwind/Just Juice with hot water.

All the food worked well. The Owairaka kumara was chewier and more fibrous than my preferred orange Beauregard variety, but in the lake, feeding is more relaxed, so more chewing didn’t waste time. After about seven hours, I was entertained that exactly 150 strokes after each feed, I would burp resonantly and with great relish; unlike the sea, there's little diversion in the lake, no jellyfish, no sharks, no bioluminescence, no fat yellow fish, and so you have to find fun where you can.

- Staying awake: the lake is a little soporific, and the

only nutrition thing I’d change, in retrospect, would be to have some more caffeine. I

brought only one Pure gel with caffeine, which I asked for at around 1pm, as I

felt in need of a wake-up. A couple more of these in the afternoon would have

done wonders, I think. Interestingly,

the jelly snakes, which always gave me a big boost during my Cook Strait and

Foveaux swims, ceased to do much for me on this swim. Maybe because the sugar

is more significant in salt water? I noticed that after the jelly snakes, I

would feel depleted well before the next feed, whereas the banana pouches

and kumara didn’t let this happen. The snack balls were always good, and

swimming in fresh water meant I could wash them down with a gulp from the lake.

- The passing of time: after three hours (I think the three-hour

mark is typically the witching hour for my swims, when I’m past the ‘warm up’

stage, and reality (‘this is going to take ages’) hits. You can only recognise

and accept that reality (which can take a while) and keep going. It doesn’t take

long for the pessimistic feeling to go away. As I’ve said, there was a rough patch early in

the swim but as soon as that was over, and particularly in the second half of the

swim, I felt calm and happy, knowing we were making good progress, and not

needing any ‘instructions’ or other external motivation.

- The island: I resolved not to look around at all during the

first hours of the swim. I knew that Motuaiko, the famous island marks

(approximately) the halfway mark of the swim; swimmers have commented that it takes a

lifetime to pass the island. During my feed stops, I deliberately looked only

at the IRB and the crew, or in a westerly direction. After one feed (I thought

I’d been keeping track of them) I asked Ben and Gráinne if we were at seven and

a half hours. No! They said we'd only just past reached six and a half hours! I took a little

look around and realised that Motuaiko was behind us. This filled me with

confidence: I still felt comfortable and confident, we were 20km down, and I

had at least another 20km in me.

- The point: the stretch between Motuaiko and Rangatira Point

(taking you to just past 30km) is infamous for being interminable. I took a few

surreptitious glances at the Point during subsequent feeds, and while it

initially seemed very far away, it came closer at a more reassuring rate

than I’d expected. From supporting other people’s swims, I knew that it took a

long time for the green blur on the Point to resolve itself into identifiably

individual trees (longer if you’re short-sighted and not wearing prescription

goggles). However, during one feed, I took off my goggles off briefly and admired

the scenery. First, I took in Ruapehu, which looks magnificent from the water.

Then, the white cliffs on the east side of the lake (Vicky had told me to look

at them), and back at the island, then the mysterious western reaches of the

lake. Finally, I looked towards Rangatira Point, and I could see individual

trees, more significantly, the big tree that stands right out on the pointiest

bit. This seemed positive, so I said to Rebecca, who was in the IRB, ‘I can

see trees!’ She firmly put me back in my place: ‘Don’t get too excited. They’re

a long way yet.’ I put my goggles back on and returned to work.

- The last seven kilometres: without telling me, as the crew like to

have their secrets, they’d masterminded a plan to get me around the Point and

into the bay nice and quickly. The lake had a lot of water in it, and Mercury

had opened up their control gates to let plenty of water out into the Waikato.

This creates a nice pull and can significantly speed up the final leg of the swim. I had to wait a little longer for a couple of feeds, so we could

get around the point (I didn’t know this, although did think it was a long 30

minutes) and start the home straight. Once we achieved the Point, the sight of rocks under the water thrilled me – the first ‘land’ I’d seen beneath me

since 3:59am – and the huge volcanic boulders looked magnificent in the crystal-clear blue

water. After a few moments to admire them, we were off again, and the lake

bottom disappeared. In this final big stretch, the water became a little

choppy, but this time the chop was helpful. Everybody seemed cheerful, and

other nice things happened: people on a passing catamaran waving at me, and

another boat giving me some encouraging blares on its horn. Very soon Rebecca

told me I had just 6km to go, ‘Balaena Bay and 1k’, which seemed doable, and –

woohoo – that it would soon be treat time (the traditional Mars Bar on the

penultimate and final feeds). Treats, however, went by the board: subsequent

feeds only had half the treats (some flat and syrupy Coca Cola), and by this

stage, I was getting quite hungry, and visions of ravioli floated in my head. We

splashed on, and then I was stopped to hear some magic words: ‘1500 metres to

go! If you can do it in half an hour, you’ll beat 13 hours. GO!’

- The finish: I set out on the great 1500m sprint feeling very keyed

up, but also quite tired. Phil, Rebecca, and Gráinne were all in the IRB

cheering and waving and whistling, and Ben was sitting up on the big boat

shouting too. Telling myself this wasn’t as far as the Splash and Dash course,

I set to work and tried moving my arms up a gear. They felt reluctant, and

while my shoulders didn’t hurt, my forearms, lungs, neck, and hips all

complained. I knew that the lake bottom would appear a long way before reaching

the beach, and decided I’d hold off kicking until I could see it. Gripping the

water also proved difficult, and my lungs objected to the new tempo. However,

with so much encouragement from the boats, no option existed other than trying

to increase the speed. I felt as if I rocketed along (later, after viewing the

video from this moment, I thought ‘surely you could find some more speed’ as it

looked laborious). The lake bottom appeared, big boulders with the occasional

catfish flitting around. The attempt at kicking was short-lived, as it gave me toe-cramp, so I let that leg dangle and kicked with the other one: I didn’t

want the cramp to go further up my leg. The Yacht Club building seemed far

away, but then I could see little sailboats in the water, and people milling

around on the beach. It entertainmed that they were just out enjoying the

afternoon, while all this drama took place in the water. A little more kicking,

and a little more arm tempo … I would swim until my fingers touched the sand,

and then hope I could stand up. The final stretch, with the sand just out of

reach (but various diversions to look at – an old bucket, a golf ball, a

mysterious pipe sticking up ready to impale me) took some time, but then my

hand hit the sand, and determined to beat 13 hours, I stood up and could walk

out of the water. Done! I heard the klaxon, the crew threw towels over me, then

some tinsel and a crown! The time was 12:57:03.

Many hugs followed, and Mark from the Washing Machines materialised on the beach, which made me wonder if I was hallucinating. In the following pictures you can appreciate how thoroughly Rebecca applied Sudocream to my face, and the rest of my body. My sunburn was minimal, just where friction had rubbed away the zinc.

I wish I could remember more about the end of each of these swims. In Cook Strait I was relieved, but also a little sad that it was over. When I landed on the sharp rocks of Rakiura last year, very out of breath after another ‘sprint’ finish, I couldn’t believe that I’d got across that stretch of water, and that it had all been so good. After Taupō I felt simultaneously exhausted and elated, and told anybody who’d listen, ‘That’s a big lake!’ It felt great to finish a swim warm: we could sit on the beach in the sun, relaxing (well, I relaxed, the crew naturally had a lot of work to do), eat the icecreams that Mark found at the service station, and smile at members of the public who wanted to know what had just happened but couldn’t really believe it when we told them.

Soon the time came to drive back to the motel, but I decided I really wanted to take my togs off as they felt full of grit. This operation required more strength and flexibility than I had: my arms had really signed off for the day. Ravioli was the order of the day at the Turangi New World: Gráinne emerged from the shop with a doomed expression,‘There was no ravioli … [wink] but I got tortellini.’ The relief!

The shower at the Tokaanu Motor Lodge delivered lots of hot water

for my initial ‘placebo shower’ where I scrubbed feebly at all the zinc,

sunscreen, grease, and lake-goo adhered to me, and hit my head on the very low

showerhead more times than was comfortable. Sitting down seemed like a good

plan, but then there was the question of trying to stand up again and climb out

of the bath tub without breaking my leg or the shower curtain. My

recommendation for every marathon swimmer is to have a clean set of pyjamas

ready for after your swim: even though I

wasn’t especially well-washed after my shower, putting on a clean pyjamas felt

the most luxurious sensation in the world. I sat to shovel some pasta and peas down

my very scratchy throat. That final sprint had clearly ravaged my tender

oesophageal membranes, but tea helped.

After a short while, Ben, who’d done some valiant IRB driving throughout the day while I splashed him a lot, arrived to sleep in one of our many beds. He had to get up at 3am to crew for another swim the next day, so we all prepared to turn in early. My room was baking hot, so I opened the windows wide, and lay down under the sheet to finish the Wordle I’d started while eating breakfast. The strain of holding my phone proved too much for my arms, so I took a little break … and fell asleep, thus losing my 85-day Wordle Streak. The night, as expected, took a long time: the temperatures turned chilly at 2am, and having fallen asleep on my back, I woke up freezing cold and completely immobilised by muscle stiffness. The quilt was well out of reach, and sitting up seemed an insurmountable task. Eventually, I rolled out of bed, tugged ineffectually at the extraordinarily heavy duvet, had a drink of water, and realised my arms were also too tired to turn the door handle and get out of the room to refill my water bottle. At 2am, I woke up again, wondering why I was still freezing but also very hot (some sunburn manifesting) and managed to wrestle the door handle using my forearms. I found a couple of plums to eat, because I was starving. The plums, while refreshing, just made me hungrier, but sleep was more important. Eventually, it was 6am and time to get up. Then I noticed the wide-open bedroom windows, which accounted for the cold. Gráinne made an extraordinarily delicious omelette, we packed up, and were on the road back to Wellington nice and early, with a short tea break at Mangaweka where we chatted a little more about the swim, among other things, and I learnt that I had indeed been deprived of my Mars Bar during the last two feed stops of my swim, in the interests of finishing sooner.

With this swim, I joined the very select group of swimmers who have completed the Triple Crown of New Zealand Open Water Swimming, and also the larger ’40.2 Club’ of those who’ve swum the length of the Lake. This is a very august company indeed, and after experiencing just how mighty that swim is, I felt overwhelmed by admiration for everybody else who has accomplished the feat. If I were to do it again, I know what I would and could do better, but meanwhile, I can think back with some incredulity that I finished.

As ever, there are many people to acknowledge and thank, not just for supporting me during the 40km swim, but for all the encouragement I received before and during the event. In Wellington, the Spud Buds and the Washing Machines for always being at the beach and ready to swim in the mornings, and then all the hilarity of post-swim coffee. There are too many individuals to name, but the members of both these groups are always ready to join in any challenge, whether it’s a two-hour swim in the middle of winter to prepare for the Ice Swim Champs, or a six-hour swim in a southerly gale. It is rare to know so many unusual souls who are both generous and obsessive about swimming in the sea, and whose enthusiasm for taking on new challenges grows by the season. For that, we must thank Dougal Dunlop, the ‘mayor’ of the Washing Machines for leading this group with such kindness and welcoming everybody who wants to swim. Timon, coach of the Bonobo swim squads, has now been keeping me on my swimming toes since 2018, and he possesses a rare capacity to imbue confidence and calm: I have learnt a lot about the process of training from Timon, and can carry this experience into my so-called ‘Secret Training’. The afternoon ‘Secret Training’ companions, especially Alicia and Gráinne, deserve special thanks too, as having a friend or two for company during all the extra swim sessions leading up to a marathon swim provides unquantifiable motivation. Summer racing is a good test of fitness and preparation – I am grateful to Nancy Prouty and Mike Cochrane for some fast, hectic racing during Splash and Dash, and the Round the Lighthouse Race early this year.

On the subject of learning, I want to thank Bre, John, Omar, Rebecca, and Victoria for letting me support their swims: each of these events was an opportunity to gain perspective on long swims. I need to thank especially supreme motivator Philip Rush for organising and directing this swim, as well as his coaching and expertise in preparation, and assembling the team of Hana and Ben for the swim itself – nothing could happen without these people.

Finally, my own devoted crew, Gráinne and Rebecca. I’ve been very fortunate that Gráinne – holder of not just one Triple Crown, but THREE (NZ, Irish, and ‘Original’) – to have been my chief cook and bottle-washer, as well as driver, hair-dryer, and purveyor of knowledge, with me for Cook Strait in December 2021, Foveaux in April 2023 (after such a lot of waiting) and Taupo. To have this ‘Titan’ of the sport volunteering to be there is very special, and I also want to thank her family for letting me have so much of Gráinne’s time. It was, too, special to have Rebecca on board for this swim: her amazing tandem Taupo swim with Bre in January 2020 gave me my first support crew experience, and first insight into the 40.2km challenge. We had our famous (notorious? Infamous?) tandem adventure in Cook Strait in March 2021, and then in 2022, I was present for Rebecca’s record-breaking double-crossing of Taupo, an extraordinary undertaking. It's impossible to express my thanks to Rebecca and Gráinne for the time, energy, and enthusiasm they have shared during the last three years.

'for to travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive, and the true success is to labour.'

— Robert Louis Stevenson, Virginibus Puerisque (1881)

Comments

Post a Comment